Using Climate Finance to Close Gender Gaps in Renewable Energy

In case you didn’t notice, we’re facing a climate crisis. As the world seeks to keep global warming under 1.5°C by 2050, this means employment in the renewable energy sector may grow to 43 million by 2050, up from 12 million today. Of those, 20 million will be hired in the solar industry alone. But how many will be women?

In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), putting economies on path to actual net zero emissions by 2050 can create 15 million net new jobs across the economy as early as 2030, of many kinds. Current employment patterns in the renewable energy sector evidence show robust demand not only for high-skilled Science Technology Engineering Math (STEM) types but also for low- and semi-skilled workers.

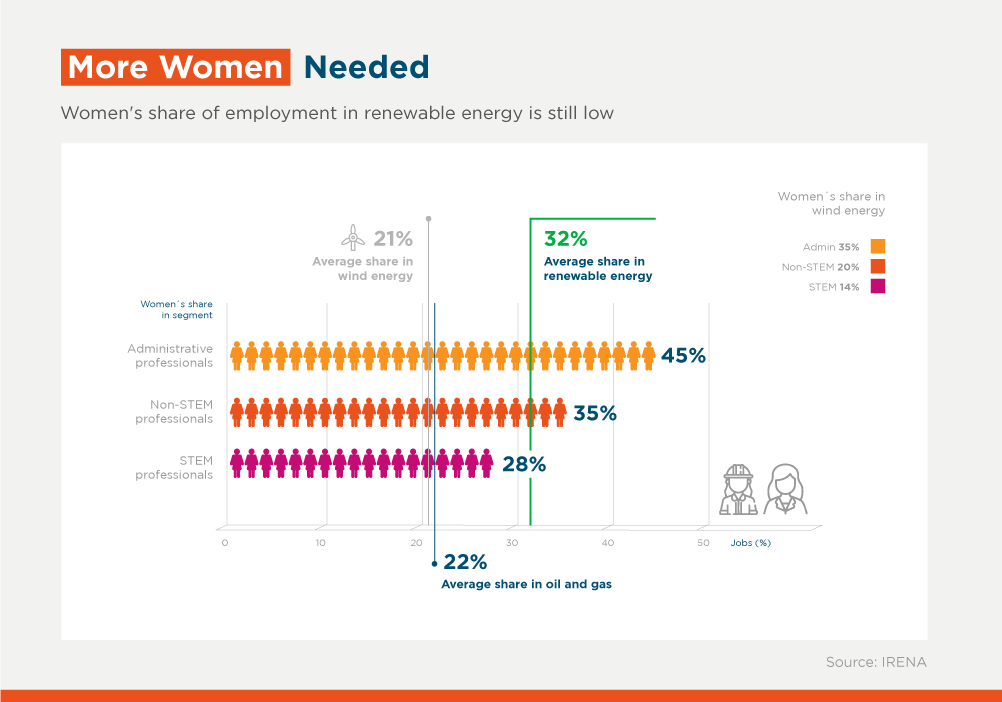

Women face hurdles to access jobs in the high-growing renewable energy industry. Today only a fifth of the workers in the global wind sector are women, a figure similar to that in the oil and gas industry. More than 80% new jobs created by the decarbonization agenda will be in male-dominated sectors. Blended finance solutions are an important tool to incentivize sponsors to take proactive steps to begin to dismantle these barriers to gender equality.

With support of donors, multi-lateral institutions and other providers of commercial finance to infrastructure projects have a unique opportunity to encourage new employment patterns. IDB Invest, for example, uses blended finance alongside its own capital and that of commercial capital from other investors to develop private sector markets, address the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and mobilize private resources into high impact projects.

Blended finance investments are particularly constructive in overcoming barriers that drive market inertia, something evident in the renewable energy sector.

Since 2014, IDB Invest has been a leader in structuring outcome-based incentives into our blended finance investments in renewable energy projects to incentivize recruitment, retention, and leadership opportunities for women in the commercial renewable energy sector. Along the way, we have learned a thing or two, about what works and doesn’t.

First, it’s hard to overstate that one of the most powerful impacts of employment incentives is simply overcoming deeply engrained scepticism about the quality and quantity of the female labor pool for STEM and/or construction roles. “There are no women” is code for women aren’t interested in these types of jobs, aren’t qualified, and we have no idea where to look for them.

Indeed, across our investments we have found that women, irrespective of education level and experience, respond enthusiastically and consistently to targeted recruitment for training and employment opportunities in male dominated fields including those for construction roles that require physical labor and/or mechanical skills. Even sympathetic sponsors express surprise at the response they get when they invest in developing recruitment pipelines instead of relying solely on traditional networks.

Incentive structures should be targeted to specific skill levels or trades that align with the financing, and they must be achievable but sufficiently ambitious to clearly necessitate new human resource strategies and investment by the sponsor. And once designed, they can be leveraged to extend to other under-represented demographics, such as afro-descendent populations. Sponsors may be hesitant of over-promising on something new, so the ultimate objective of incentive design should be to support the sponsor through its own self-discovery process.

Holistic changes to organizational culture are achievable. A well-designed incentive structure, especially when married with technical assistance, can reach beyond recruitment targets and elevate gender as a strategic imperative for the executive leadership. Discreet contractual deliverables such as board resolutions, new organizational policies and strategies, gender certifications, training programs, and human resource targets can be mutually reinforcing, producing organizational outcomes beyond the narrow scope of the contract.

With a tiered incentive structure and technical assistance support, Central Puerto in Argentina, the sponsor of two of the first wind projects in the country, designed a board approved gender action plan that included increasing to 50% the number of female applicants to all vacancies, The goal, supported by the larger organizational initiative, led to a remarkable 67% of hires in 2021 to be women, clearly surpassing their 30% plan target.

Outcome-based incentives at the project scale can have surprising influence on public policy discourse on the promotion of women’s employment. Incentive structures in commercial deals cannot be designed around this outcome, but multi-laterals and donors can be mindful that the nexus of infrastructure and labor is an important topic for policymakers (and unions), and high-visibility projects or successes can have ripple effects in national discourse.

For example: a public tender for a utility scale solar photovoltaic project in Uruguay in 2019 contained explicit requirements for the inclusion of female labor in construction. The structure of these targets replicated that developed three years earlier by IDB Invest with resources from the Canadian Climate Fund for the Private Sector in the Americas (C2F) for Casablanca & Giacote, one of the first solar projects in the country. It was precisely that well-documented success and the knowledge that a trained female labor pool now existed in the country that likely gave the government confidence to set similar thresholds for the 2019 tender.

The last few years has seen increasing attention paid to gender issues by investors. Development finance institutions and commercial banks have signed onto the 2x Collaborative, and gender has risen to the consciousness of institutional investors as part of a broader appetite for investments with Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors. Marrying gender and climate change objectives can no longer be viewed as a distraction, but rather a selling point for sponsors raising capital, as well as a critical path for donors and multilaterals to support both greater growth and greater equity in local infrastructure supply chains.

LIKE WHAT YOU JUST READ?

Subscribe to our mailing list to stay informed on the latest IDB Invest news, blog posts, upcoming events, and to learn more about specific areas of interest.

Subscribe