Nudging People to Save Water through the Private Sector

Every year on March 22, World Water Day serves to raise awareness of the 2 billion people currently living without access to safe water. And water scarcity is a growing problem worldwide: an estimated 9% of the global population could be forced to move due to severe water shortages by 2030.

Although Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is home to more than 30% of the world’s freshwater resources, many countries still face water scarcity driven by increasingly severe droughts, overuse by productive sectors, population growth, inefficiency in water treatment, among other factors. Domestic consumers also have a role to play in guaranteeing water sustainability.

But how? How can people change their behaviors to use water more efficiently? What role can private sector water providers play in encouraging their customers to use less water?

Given the fundamental human right of access to affordable clean water, traditional market practices such as increasing prices to encourage water conservation are not always desirable. That’s why strategies that can help people change their water use behaviors voluntarily are key for both the private sector and policymakers.

In order to nudge people to use less water, behavioral interventions first need to understand the different barriers that can influence people’s actions. For instance, some people may place more value on the immediate comfort of using as much water as they want today versus the potential future consequences of drought-induced water scarcity (present bias). Others may choose not to save water since they don’t think that their friends or neighbors are doing so either (social norms).

Evidence shows that strategies focused on social norms can be a low-cost way to reduce household water consumption. For example, an intervention in Costa Rica that used messaging to compare a household’s water consumption to its neighbors helped decrease consumption by nearly 5%. Similar approaches using social comparisons and water-saving recommendations have also been effective in the United States, leading to significant reductions in water consumption. However, as pointed out by a study on water consumption in Australia, changing people’s behavior is not easy, and requires, among other things, the identification of specific segments within communities where it is feasible to influence behavior.

Tapping into the source of water use behaviors

BRK Ambiental, one of the largest water and sanitation companies in Brazil, is working to promote water conservation practices among its customers. To this end, IDB Invest and the IDB Behavioral Economics Group are working together with the company to better understand the barriers people face when it comes to saving water and design behaviorally-informed strategies to address them, starting in the city of Limeira, São Paulo.

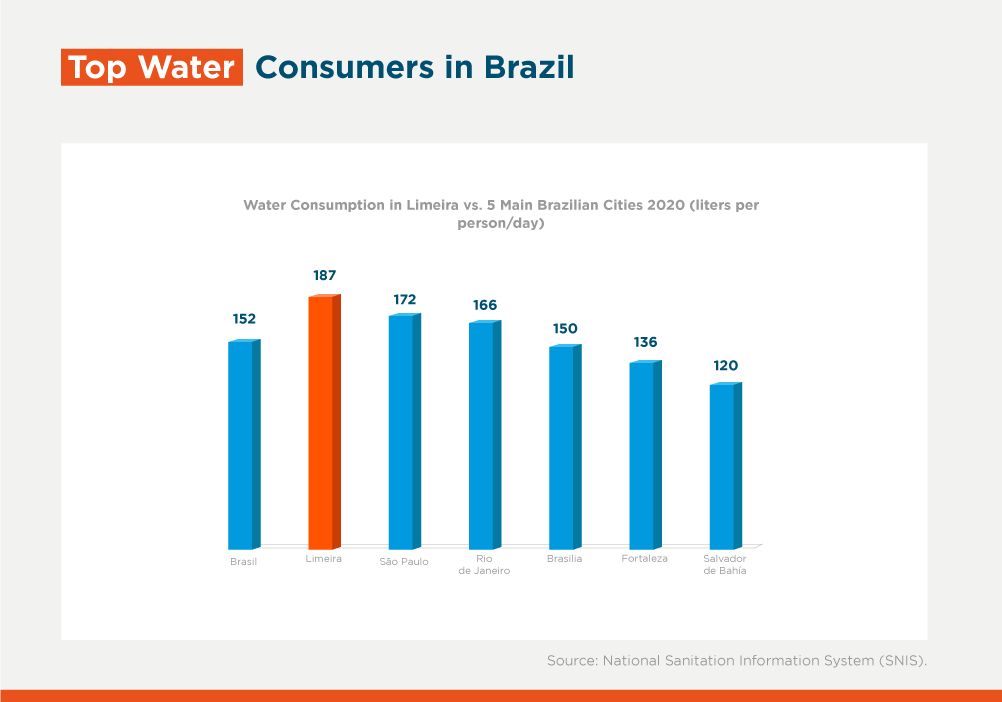

Limeira has a high rate of coverage for drinking water and sanitary sewerage at 97%, and its per capita water consumption is also high: in 2020, residents of the city consumed 187 liters per day, almost 35 liters above the average for the rest of Brazil. Even though Limeira has experienced a stable supply of clean water to date, and water losses due to infrastructure issues are below the national average, water supply in Limeira and neighboring areas will likely be affected in the coming years by climate change and population growth. This makes strategies to promote conscious household water consumption even more relevant, which is why BRK Ambiental is taking action.

As a first step, we recently carried out a series of interviews and focus groups with BRK customers to understand their consumption habits. Participants were grouped according to average consumption levels (low, medium, high) to assess any potential differences in water conservation practices and perceptions depending on usage. We set out to gather information on four main topics: (1) perceived economic consequences of not saving water; (2) perceived social norms in Limeira about water consumption and conservation; (3) importance of information availability and recommendations to encourage saving water; and (4) perceived benefits of saving water.

We captured three main insights from this exercise. First, messaging matters. Participants don’t seem to take the time to read the information available in their water bill, which includes their historical consumption trends and the different price brackets that they could fall into depending on their consumption level (i.e., the more they consume, the higher the cost per m3 of water). Improving the messaging and design of water bills with human behavior in mind could be a way to encourage people to save water.

Second, cultural and social norms matter. Participants indicated that even when they think others are using water irresponsibly, they don’t feel comfortable saying so, except to their close friends and family. Finally, cost isn’t always an issue for them. Some participants indicated that they tried to save water to lower their bill, while others were indifferent to bill fluctuations. This mixed evidence would need to be further assessed to understand the role of pricing in this particular context.

What’s next?

Based on these initial results, we’re continuing to work with BRK to design a behavioral intervention to help reduce water consumption among households in Limeira. We also plan to rigorously evaluate the impact of this intervention, with an eye towards scaling what works best in other cities that the company serves.

LIKE WHAT YOU JUST READ?

Subscribe to our mailing list to stay informed on the latest IDB Invest news, blog posts, upcoming events, and to learn more about specific areas of interest.

Subscribe