IDB World: Working from Home, Solar Panels in the Amazon, the Middle Class

Can a WFH approach help achieve sustainable recovery and net-zero-emission economies?

Since the new coronavirus hit us last year, forcing countries into social distancing and isolation, companies and governments have adopted new policies to work from home (WFH). These periods of isolation have led us to the unprecedented situation of having more people than ever before working from home to reduce the risk of spreading and contracting the disease.

While much has been published about how remote work is revolutionizing the way we work, little has been said about how it can contribute to a post-pandemic sustainable recovery and net-zero emissions by 2050.

Although the positive environmental impact of lower air pollution and fossil fuel use due to decreased traffic volumes caused by people not driving to work will be short lived, as economies are reopening, there is great potential for WFH practices to continue contributing to a more sustainable future.

Many of us, who are already lucky enough to be able to work from home safely, have noticed that remote work has not undermined our productivity in those sectors that can afford a WFH approach. WFH, remote learning and on-demand digital platforms have pervaded the region. Thanks to the technological progress, a large portion of the working population could go on working.

Innovation, Technology and Energy in the Bolivian Amazon Rainforest

On the shores of two of the most important rivers in Bolivia, Madre de Dios and Mamoré, lie sister towns Riberalta and Guayaramerín, in the department of Beni, Bolivia. Over 500 households are transforming their lives in these towns in the North of the Bolivian Amazon rainforest. Solar radiation has become an ideal resource to deliver clean, renewable energy through photovoltaic solar panels.

Have you ever wondered how certain communities still survive with no electrical power? Apart from being deprived of a reliable, safe source of light at nighttime, what happens when people have no access to information and entertainment? Amid a world pandemic in the 21st century, it is essential to have access to information and basic services.

These types of scenarios are common among families in the remote communities of Riberalta and Guayaramerín, where 90% of the population have access to power. However, in the areas that do have electricity, it is generated from diesel.

In order to change this, the IDB, through a program to provide electric power to rural areas, has helped the Bolivian authorities to finance the purchase of 500 photovoltaic solar systems for the families in Guayaramerín and Riberalta. This project is also helping manage the delivery of another 1,200 units to the departments of Tarija and Beni.

Read on: https://blogs.iadb.org/energia/es/innovacion-tecnologia-y-energia-en-la-amazonia-boliviana/

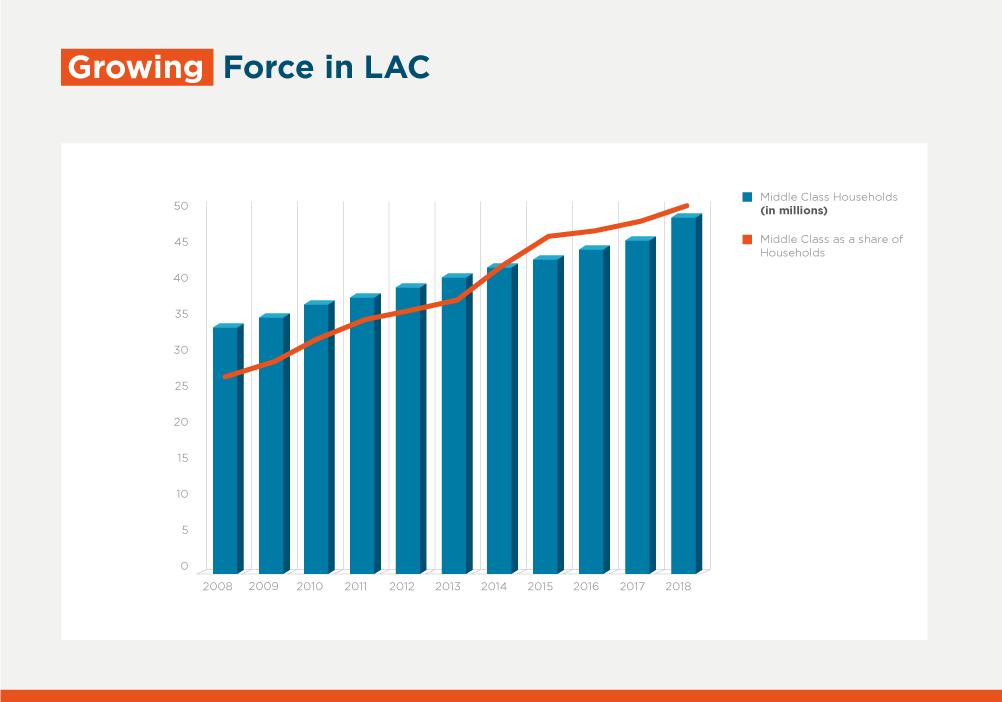

The Elusive Middle Class in Latin America & the Caribbean (LAC)

Economics Nobel laureates Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee raised the following question in 2008: What’s a middle-class household in a developing country? In order to answer this, they analyzed the results of interviews carried out in households from 13 low- and middle-income countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America. They explored their consumption behavior in terms of food, education, healthcare and entertainment; occupational and employment patterns; entrepreneurship and access to credit; migration and fertility, etc. They concluded that: “Nothing seems more middle class than the fact of having a steady well-paying job. (...) The reason why this matters —indeed why it might matter a lot— is that it leads us to the idea of a ‘good job.’ A good job is a steady, well-paid job —a job that allows one the mental space needed to do all those things the middle class does well. (...) Perhaps the sense of control over the future that one gets from knowing that there will be an income coming in every month – and not just the income itself – is what allows the middle class to focus on building their own careers and those of their children.”

A decade after this paper was published, the situation is Latin America is bittersweet. On the one hand, there was a very good reason to celebrate: after years of steady fall, monetary poverty had reduced substantially. Between 2002 and 2018, the percentage of people in Latin America with income under the poverty line (five dollars a day as per the standard in the region) fell from 42.3% to 23.1%. Even though some countries came out more successful — Bolivia, Ecuador, Paraguay — than others — El Salvador, Honduras and the Dominican Republic — the trend could be felt everywhere.

On the other hand, however, there were also matters of concern. In 2019 only 4 out of 10 Latin Americans on middle income were far enough from the poverty line; the rest lacked a buffer to protect themselves from falling back under the line in case of a deep recession. This vulnerability was associated with the quality of their employment. Unlike Duflo and Banerjee’s ideal, very few workers earning middle income in Latin America (third income quintile) have experienced work stability. In 2018, less than a third of the workers with middle income in Bolivia and Colombia had permanent contracts and over 40% were self-employed. Given the fact that access to social security in Latin America has historically been linked to formal wage-earning work, a large portion of the middle class workers have risked losing their income due to illness and unemployment and have no access to a pension when they retire. Thus, in Chile, for example, 30% of the workers with middle income did not contribute to social security in 2017. In Argentina this number reached up to 46%, whereas in Peru, Bolivia and Guatemala, it went over 80%.

Read on: https://blogs.iadb.org/trabajo/es/la-esquiva-clase-media-latinoamericana/

LIKE WHAT YOU JUST READ?

Subscribe to our mailing list to stay informed on the latest IDB Invest news, blog posts, upcoming events, and to learn more about specific areas of interest.

Subscribe