Dissecting the Confidence Crisis: Mexico’s Alternative Lenders

As some of Mexico’s major alternative credit providers (locally known as SOFOMs) have fallen from grace over the past few years, multiple lessons have been learned that can be used to ensure that the country’s micro and small entrepreneurs and most vulnerable segments maintain access to much-needed financing.

From accounting mistakes and oversights all the way to alleged fraud, the ripple effect from the collapse of some of the largest SOFOMs (AlphaCredit, Crédito Real, MexArrend, Unifin, Progresemos, Alternativa 19 del Sur, among others) is quite evident. The whole sector is facing a severe investor confidence crisis. Fitch recently pointed this out in its revision of the sector outlook for Mexican non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs), with a downgrade from Stable to Deteriorating, citing “the revision reflects Mexican NBFI issuers’ reduced ability to fund credit growth or efficiently refinance maturing debt. Given the management and governance shortcomings that contributed to Credito Real and Alpha Holdings’ defaults increased financial disclosures and transparency (are) critical to rebuilding investor confidence in the sector.”

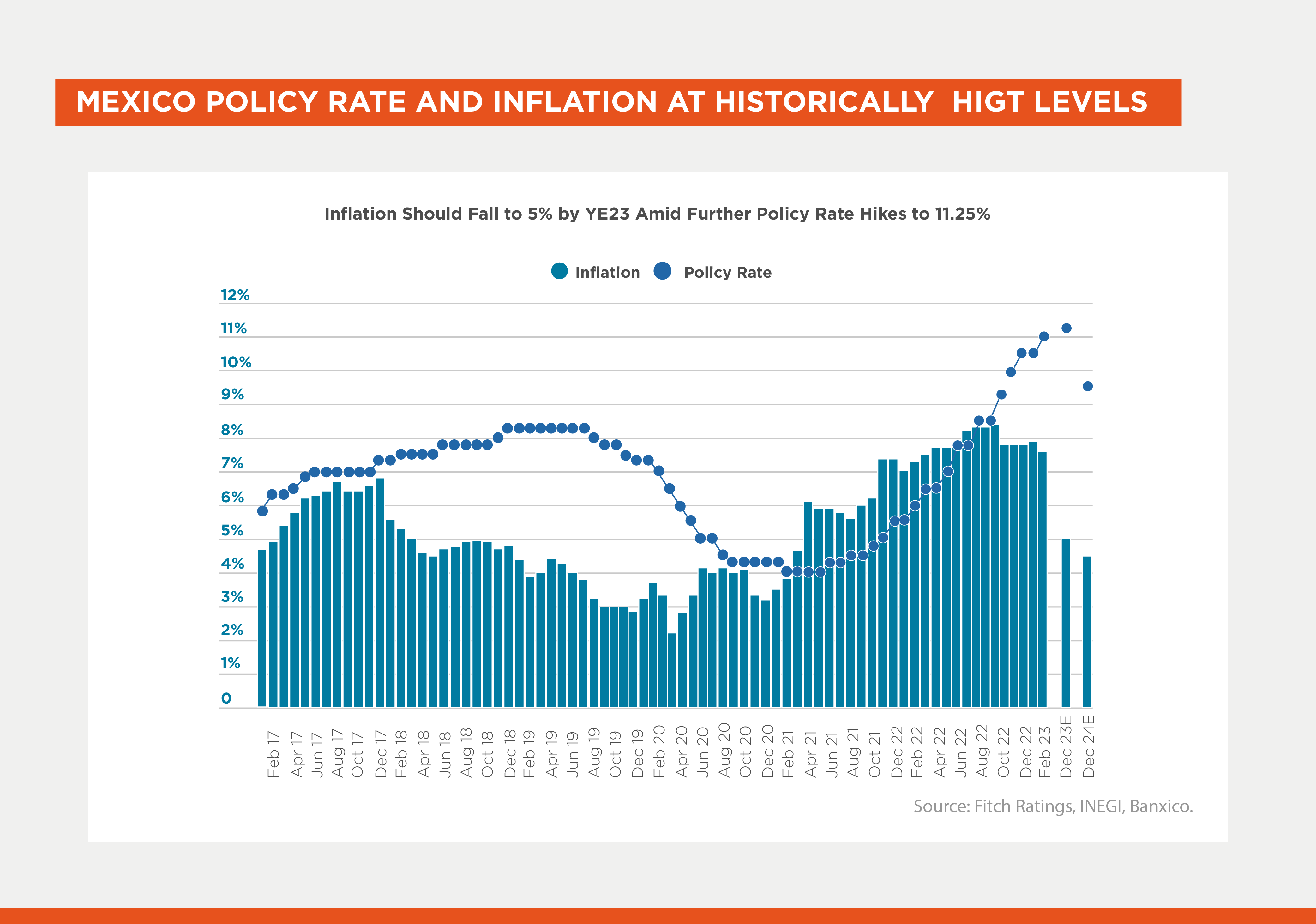

Numerous SOFOMs (non-deposit taking financial institutions), leveraged their ability to deliver exponential growth to attract sizeable tickets from domestic as well as international lenders and investors. Some of the major macroeconomic adjustments (rising interest rate environment, retrenchment in liquidity on a global scale, peak inflation) during the post-pandemic era not only deteriorated some of the underlying conditions for the SOFOMs but also left the sector exposed: lack of proper regulation, irresponsible origination practices, accounting misconceptions, debt cliffs, local funding sources being systematically shut down, among others. Investor confidence quickly eroded and has yet to show any signs of improvement. Is the confidence crisis over for the Mexican SOFOMs?

First, let us take a breather and examine the situation with a narrower lens. The current confidence crisis is not a widespread financial crisis and/or an economic collapse: the banking sector remains strong, deposit-taking financial institutions (SOFIPOs) are stable and it appears that the Cajas (cooperatives) are on a positive path towards continued growth and innovation. SOFOMs, the current epicentre of the confidence crisis, are not to be easily dismissed as they account for 3.1% of the Mexican Financial System and undertake a fundamental role in reducing the financing gap through a gender lens to micro and small entities in the country.

Second, this crisis may – as it is often the case – throw the baby out with the bathwater; in other words, over-generalization can lead to eroding confidence and that tends to spread just as fast a highly contagious disease. Many non-bank financial institutions, including SOFIPOs, Cajas and supervised/regulated financial entities are in danger of being misidentified as problematic cases when they should necessarily be deemed as such. The contagion effect in financial markets is real, which is why it is critical to appreciate the nuanced dynamics of each of the verticals withing the financial system.

There is room to be cautiously optimistic. The Mexican shadow banking system is ample, deep and dynamic; the time is ripe for other institutions to step-in and to cover the vast vacuum left by recently departed players, allowing for a continued flow of much-needed funds to some of the most vulnerable segments of the population and to unbanked and underbanked MSMEs.

The aftermath of this crisis has to be closely followed. The recent financial turmoil in the sector pushed lenders to reconsider collateral structures, shifting their preference for secure structures in order to participate in the funding of some of the aforementioned financial institutions. Investors (including development finance institutions (DFIs)) are falling back into tried-and-tested safe havens during times of crisis: secured facilities with visibility and control of the flow of funds from collateralized loans, corporate guarantees from robust, well-funded parent companies, the use of special purpose vehicles and more sophisticated structures like master trusts with a lockbox mechanism and warehouse facilities, to name a few.

There are select opportunities to explore and develop: new entrants (fintech and alternate lenders – innovators and growth institutions) that are revolutionizing the market with cutting-edge digital platforms and product offering, existing borrowers (regional and local leaders) aimed at targeting low-income households and vulnerable segments, as well as other prospects that proved to be resilient.

A smaller yet relevant segment of the Mexican financial system are the Cajas, otherwise known as the cooperatives. In Mexico, this ecosystem is comprised by approximately 154 licensed entities out of which close to 40 have over 30,000 members. Their assets are roughly equivalent to 2% of the Mexican financial system (when measured by total assets). Cooperatives benefit from their ability to attract “sticky” money, leveraging their well-established nature as reliable deposit-takers, and typically have excess liquidity to deploy as deposits are sufficient and growing – deposits are insured by a mechanism that operates in a similar fashion to the IPAB (deposit insurance entity that guarantees bank deposits) although with notable differences in insured amounts.

Relatively new entrants, often fintechs, are capturing investors’ attention through their technology-based business models that are rapidly reconfiguring the financial landscape and financial service offering across the region. This fast-paced ecosystem allows multilateral institutions like IDB Invest to play a critical role in not accompanying but also supporting the continued development and growth of such players during their early stages through maturity.

The financial downturn of such a relevant segment of the financial system certainly reshuffled underlying dynamics and, perhaps, changed the status quo for years to come. While this recent sectorial quandary casted a [temporary] dark veil for some, it shined the light on other segments as well as new market entrants. The Mexican financial system is too broad, too deep and too complex for it to be bucketed into one simple idea; generalization can lead to misconception, a risky endeavour with a significant opportunity cost.

More importantly, financial intermediaries across different segments continue to strengthen their environmental, social, and corporate governance agendas as investors and lenders continue to carry out their commitment to sustainability and positive developmental impact – the Mexican financial system has a myriad of investment opportunities that can create considerable developmental impact; some are yet to be explored.

All in all, it is essential to parse through the Mexican financial market with a critical filter, especially now when the storm is still not over. Unsurprisingly, by conducting this exercise, there is strong evidence that points towards greener pastures, entities that are subject to prudential regulation are performing significantly better than those that are not regulated.

LIKE WHAT YOU JUST READ?

Subscribe to our mailing list to stay informed on the latest IDB Invest news, blog posts, upcoming events, and to learn more about specific areas of interest.

Subscribe