The Hurdles of Minority Shareholders Looking into Exits in LAC – Be Mindful!

Here’s a little-known detail about 2020 and the first half of this year: it was a record year for capital moving in and out of private companies in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). And this was despite the well-known hurdles often suffered by minority shareholders trying to exit their investments in the region.

With economies contracting all over because of pandemic-related lockdowns, the engine behind this trend was a world with excess liquidity due to record-low interest rates in developed markets. The pandemic created attractive investment opportunities particularly in venture capital (VC) tech-related businesses, just as we are seeing LAC’s private-capital industry maturing.

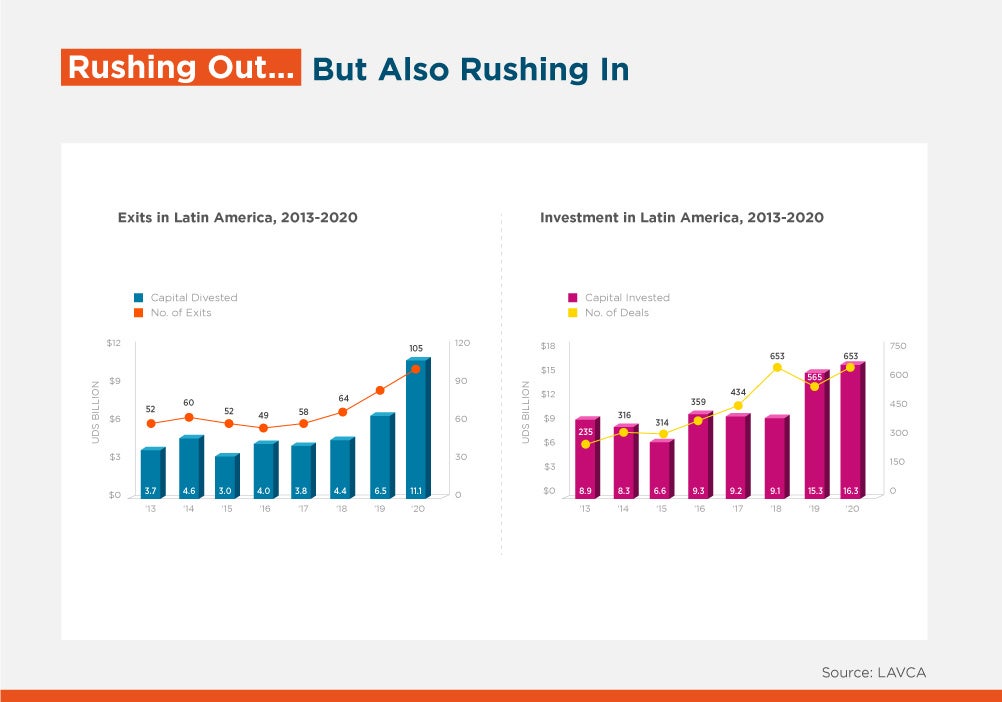

In 2020, the private capital[1] industry in Latin America demonstrated resiliency amidst the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic disruption across the region. Fund managers invested $16.3 billion across 653 deals in 2020, a record in statistics compiled by LAVCA, the Association for Private Capital Investment in Latin America.

According to LAVCA, 2020 was also a record year for exits, driven by public markets activity on the Brazilian B3 stock exchange. Private capital fund managers divested $11.1 billion in 105 exit deals. Similar to what occurred in developed markets, historically low interest rates drove capital to equities creating a receptive market for initial public offerings. As a result, private capital fund managers utilized public markets mainly in the US and Brazil as a path to liquidity.

LAC did see a lot of investment activity, but it could – and arguably should – have grabbed more of the action, and steps must be taken to correct this. One key problem is the difficulty to cash out of private investments. In the 2020 edition of EMPEA’s Global Limited Partners Survey, produced in collaboration with LAVCA, 22% of respondents cited concerns about the exit environment as a deterrent to investing in the region, a percentage that has remained steady throughout the past few years of the survey reflecting a proportion of subpar exit outcomes and trapped capital.

According to an EMPEA/LAVCA report, the region has a five-year private capital penetration rate of only 0.18% compared to 1.86% in the United States. In a region where access to bank lending is scarce, private capital has a vital role to play in providing businesses with long-term financing to address local consumer and industrial demand. Such a low private capital penetration in LAC could be linked to the fact that traditional private equity and VC financing structures pose inherent challenges for fund managers, including the shallowness of local capital markets as it limits the number of possible buyers. Also, there are significant drawbacks for minority partners that often have limited rights under local law and as such are subject to a weak relationship with a majority shareholder.

The fact that many investments in emerging markets have tended to be and still are minority growth equity deals can also complicate exit routes as, at exit, alignment between company sponsors and minority shareholders can be hard to create, and the sponsor typically has a lot of leverage in the decision-making process. With many companies being controlled by families in the region, it is also quite common to see a situation in which a minority investor wants to exit a minority stake in a family business, but the family isn’t aligned and won’t let go. Similarly, while selling back to the promoter is an option often written into the terms of original deals, investors may not see it as the most attractive option, and at any rate, some may have trouble enforcing it. Such cases sometimes take years in court to sort out – rendering it an unviable path to exit.

The combination of the lack of market for the sale of the shares and the strong legal rights of the majority with a different time horizon for exit, are the perfect cocktail to end in a judicial process or arbitration with high agency costs for shareholders and the company.

Finding appropriate exit windows is difficult too for minority partners. All this contributes to making it harder for investors in non-listed companies to consider their experience in the region’s emerging markets a resounding success. So, what must be done?

The key instrument to regulate a minority shareholder's rights in an investee company is a Shareholders' Agreement, which should include different scenarios for their exit. A good agreement includes multiple features, including minority protection rights such as: (i) the nomination of a board member or observer representing the minority partner; (ii) an outline of corporate actions requiring consent of minority shareholders or a super-majority; (iii) preemptive rights to purchase newly issued stock before it is offered to others, to avoid possible dilution; (iv) and reporting covenants so that information on operations is available to all.

Most importantly, the agreement must also specify exit rights, such as transfer rights (the right to be able to sell the shares when it deems appropriate, to maximize returns on investments). On the other hand, features such as call options and drag-along rights (which may force a sale of the minority position at the wrong time), Rights of First Offer (“ROFOs”) and Rights of First Refusal (“ROFRs”), which limit the scope of possible buyers of minority stakes, should be strongly resisted or adequately mitigated when possible (e.g. set a minimum IRR if call options and/or drag along rights are accepted by the minority shareholder) – although ROFOs are friendlier than ROFRs for minority shareholders.

Let’s not forget about put (sale) options, sometimes referred as the “necessary evil” – the right to sell shares to others under certain pre-agreed conditions, providing a liquidity mechanism for the shares, but not guaranteeing a return on the investment. Tag-along clauses, the right to sell if and when certain other shareholders sell, on the same terms and conditions (including price), are also deemed as a key exit right to protect minority shareholders.

In summary, minority protection and exit rights are key to investing in privately held companies as a minority shareholder. Sophisticated investors such as fund managers and many institutional investors have learned long time ago about these the above-mentioned hurdles. However, this is the time, as the private equity industry develops in LAC, to ensure that those individual minority investors willing to continue helping the region recover from the pandemic will have the necessary protections and rights to try to overcome the exit hurdles of the past. If you feel identified with these hurdles, be mindful at the time of investing and get appropriate expert advice.

LIKE WHAT YOU JUST READ?

Subscribe to our mailing list to stay informed on the latest IDB Invest news, blog posts, upcoming events, and to learn more about specific areas of interest.

Subscribe